This is part three of a series on Knowledge Management. We revisit why we view knowledge management as a core competence of Embrace IT, what that means, and what we are doing to build our learning capability from first principles.

We've discussed how knowledge contains both tacit and explicit elements, and requires an audience to meaningfully engage with it. With this distinction in mind, we can revisit the idea of lifting knowledge from the individual to the organisational level.

Lifting knowledge to the organisational level implies that knowledge can reside among multiple people at the social level. What does that mean? A common example of social or group-level knowledge is that of a shared set of rules and norms. Organisational culture, shared experiences, or informal routines and processes are forms of tacit collective knowledge (Spender, 1996; Hislop, Bosua, & Helms, 2018, pp 20-22).

Complementary knowledge is another form of collective knowledge. It derives from the interdependencies between individual knowledge of members in a team or organisation. In a scrum team, for example, there is a shared understanding of who knows what, and what the group reasonably can and cannot do. The team learns how to coordinate their specialised division of knowledge to solve problems (Hecker, 2012).

While all this tacit social knowledge is ultimately still contained within individuals, it is distinct from individual knowledge because it isn't bound to any single member of the community.

Group-level knowledge can also be explicit. Think of documentation, formal rules and operating procedures, roles and hierarchies. We can think of this as objectified knowledge (Spender, 1996). It is contained within artifacts rather than individuals (Hecker, 2012).

So - bear with me - we've distinguished between tacit and explicit knowledge, both of which can reside at the individual level and the group level. Explicit group-level knowledge is objectified and artifactual. Tacit group-level knowledge is collective and complementary. Now to the real question: how do we get knowledge from the individual to the group, and back?

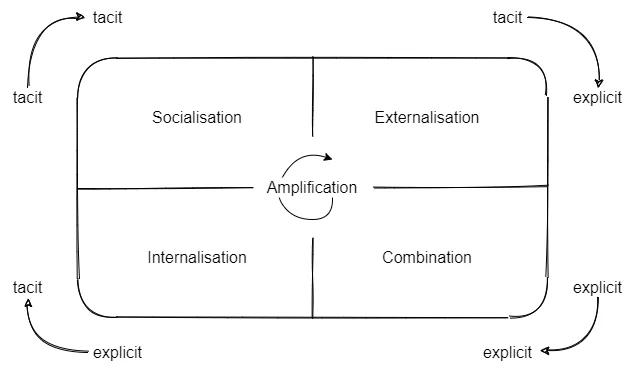

An often used conceptual model for knowledge creation is SECI (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995): socialisation, externalisation, combination, and internalisation.

Socialisation is the process by which members of a team or community share and create tacit information - a shared understanding through observation, mimicking and working together.

Externalisation objectifies some of this tacit knowledge, allowing it to be shared more easily and moving ownership from the individual to the collective.

By combining existing sources of explicit information, new explicit knowledge is generated. The body of collective knowledge grows in complexity over time to an organisational body of knowledge.

This body of knowledge is in turn internalised by individuals, embodying it in their daily work and practices. Internalisation allows an individual to make use of the acquired explicit knowledge, but it also is the process by which collective and complementary knowledge is reinforced.

The cycle repeats, as internalised knowledge is shared and added to through socialisation. During the cycle the level of knowledge of the group as a whole has been elevated, and knowledge has moved 'up' from the individual to the organisation. (Hislop, Bosua, & Helms, 2018, pp. 112-114)

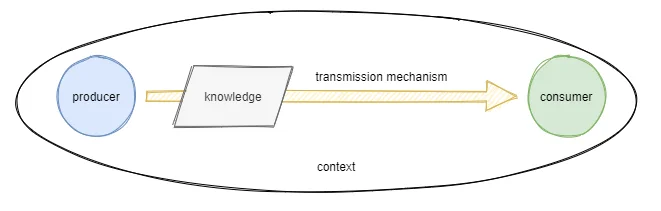

The exact mechanisms through which knowledge creation and transfer takes place vary. Think of face-to-face collaboration, teaching and tutoring, or codification and providing access to information. There isn't one catch-all mechanism that can satisfy all four steps of the knowledge creation process. Yet all mechanisms we can think of need to satisfy a common set of prerequisites in order to be effective. This is the so-called conduit model for knowledge transfer, consisting of five elements:

Absence or misalignment of any one of these components can disrupt knowledge transfer. (Hislop, Bosua, & Helms, 2018, p. 24).

We're starting to get an idea of how hard this learning capability is to build and get right. Knowledge creation goes through four stages that each take time and effort, and require different transfer mechanisms. And every transfer mechanism needs to get all five conduit elements right in order to be effective. At least now we have a basis for understanding why knowledge transfer may fail, and can take steps to make it more effective in our organisation.

Unfortunately, the SECI and conduit transfer models are part of what's derisively known as the optimistic view on knowledge transfer. There are a number of objections and complications that we need to address first.

Hecker, A. (2012). Knowledge Beyond the Individual? Making Sense of a Notion of Collective Knowledge in Organization Theory. Organization Studies, 11(3), 264-278.

Hislop, D., Bosua, R., & Helms, R. (2018). Knowledge Management in Organizations: A Critical Introduction (4th ed.). Glasgow: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Spender, J. (1996). Organizational Knowledge, Learning and Memory: Three Concepts in Search of a Theory. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 9(1), 63-78.